I

I keep an eye out for interesting headlines in the supplement and nootropics world, but unfortunately I’ve learned you have to take them with a grain of salt. Here’s one that passed through recently and that sparked some discussion among my friends: “Brain-Boosting’ Supplements May Contain Unapproved Drugs, Study Says.”[1]Carroll, Linda. “‘Brain-Boosting’ Supplements May Contain Unapproved Drugs, Study Says.” Accessed January 29, 2021. … Continue reading Sounds scary! No one wants to pop a multivitamin or a magnesium supplement thinking that it might be mixed with random drugs. Problem is, this is a fine example of where the headline is tuned to make it sound far worse than the actual study data supports. The cited news article (and similar ones on other sites) includes further fear-inducing words like “unapproved,” “dangerous combinations,” “prescription drugs in other countries but not the US,” etc.

I went to look at the underlying study to see just what data these articles used as a basis, which has a rather incendiary title itself of “Five unapproved drugs found in cognitive enhancement supplements”.[2]Cohen, Pieter A., Bharathi Avula, Yan Hong Wang, Igor Zakharevich, and Ikhlas Khan. “Five Unapproved Drugs Found in Cognitive Enhancement Supplements.” Neurology: Clinical Practice, September 23, … Continue reading I have some issues with how the data is presented which I’m going to cover, as well as point to some larger issues I’ve noticed in the supplement and regulation world.

For one, that title! “Five unapproved drugs found in cognitive enhancement supplements” might have you thinking your Vitamin D3 is mixed with amphetamines. I find it academically dishonest, however, as they specifically chose exactly one set of products to investigate: those based on noopept. Noopept is a piracetam analog, and there’s rat research showing it increasing BDNF levels in the brain. I haven’t researched and tested it myself yet, though piracetam is well-studied and generally safe (with a history going all the way back to the fellow who came up with the name nootropics, discussed in my post on defining the term nootropic).

Now, before I come down too hard on this, I’m going to start this by saying the actual study methodology is fine. They used a handful of dietary supplement databases to find 10 products listed as containing some variation of piracetam, then ordered them in September 2019. They then went to medical-grade manufacturers to get pure samples of these nootropics (you can find their full list of those providers at [3]links.lww.com/CPJ/A206). Finally, they ran the products through liquid chromatography to compare purity and check if these product makers were mislabeling. So far so good.

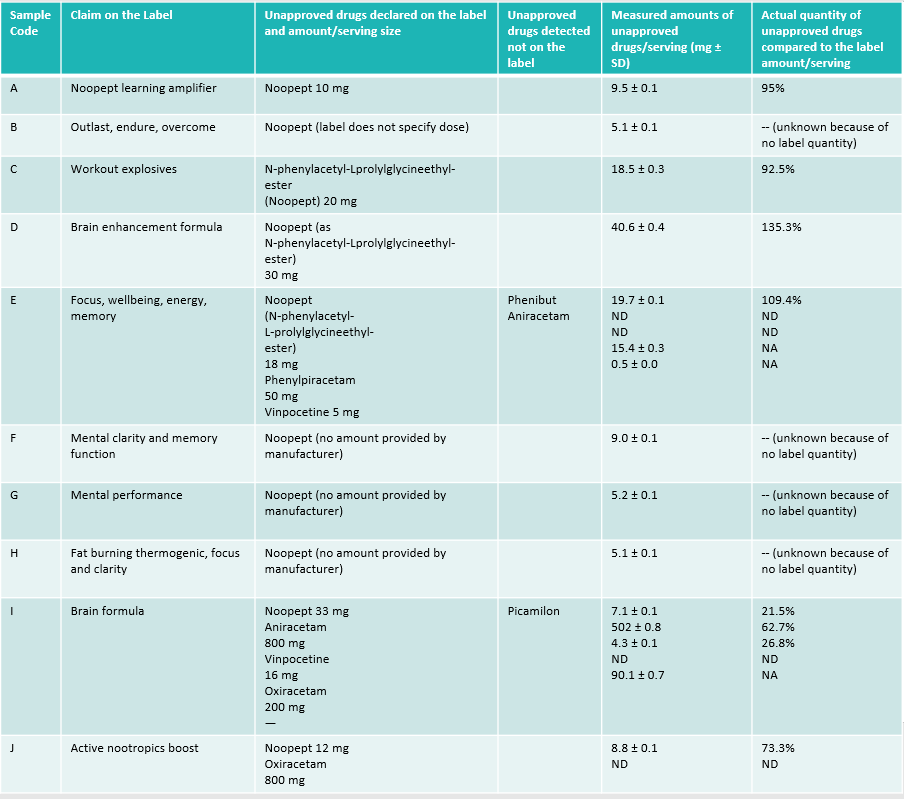

My issues are with how they spun the data, which in turn news sites picked up and emphasized. Their paper presents the following chart, which I’ve redrawn for this site and highlighted several parts that jump out. I copy/pasted all of their own column headers, word choices, etc. I removed a couple columns that add more noise than signal (the ones about the serving sizes on the labels). There are several problems that jump out at me, described below.

Transcription of the table on page 3 of the study. I kept all wording the same, and omitted several irrelevant columns

“Unapproved” Drugs

Both throughout the paper and in this chart, they repeatedly harp on the “unapproved” nature of this nootropic. I’ve ran into this same ambiguity online, where people hear unapproved and freak out about something’s safety. First though, who’s doing this approving? Well, in the US the FDA has dominion over medical approval. Anytime you hear a US paper, news story, web site, etc. talk about something being unapproved, they’re usually talking about the FDA’s metric (or the lack thereof).

The FDA has a defined process that any new drug needs to go through. If you’ve ever heard the phrase “stage 3 clinical trials”, that’s what it usually takes to get their stamp and the ability to claim something is approved. The FDA doesn’t do these trials pro bono, however, rather they must be paid for and sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. Companies justify the expense by being able to then sell their approved drug via patents. That’s why a new drug is only available from the original company, until the patent expires and generics enter the marketplace.

Meanwhile, your supermarket’s supplement aisle is littered with natural substances with the disclaimer “not approved by the FDA.” Reason being, you can’t patent natural substances that have been on the market for years. So, with no one willing to sponsor them for trial, they’re going to remain that way.

That’s why you shouldn’t take the phrase “approved”/”unapproved” so seriously as news articles suggest. Don’t get me wrong, there’s something to be said for the extensive trials that prescription drugs go through. While they have their own issues, it’s generally a good sign that at least they’re not toxic (Though they can be more informative than supplement surveys alone). Conversely, just because no pharmaceutical company has sponsored these trials doesn’t mean that something unapproved is unsafe.

For the purposes of this study and the sites reporting on it, the root of my issue is the authors putting the word unapproved in the title, when many/most readers will assume it means it’s dangerous. It doesn’t, it just means no one has had financial incentive to sponsor FDA clinical trials.

What About the Products Themselves?

The study provides a table of the 10 products they tested listed with sample codes, however, they declined to name the actual products. I can see why, due to potential legal challenges. I went hunting to see what I could find by searching for the “Claim on the label” field in the study. I located a likely product for 3 of those 10, however, I can’t be certain I found the exact ones so I’m loathe to guess. For the other 7, the taglines were ambiguous and I found multiple possible options but without any of them referencing noopept.

For the 3 I did find, 2 are available on their manufacturer’s site only, so I doubt they’re seeing much traffic (assuming you can even still order them). The 3rd I did find an active Amazon listing. The catch, though? Those 3 active ones are–guess what–the 3 roughly near their actual label values of noopept content, with the worst having ~73% of its claimed amount. That’s a bit much (I expect +/- 20% from the label claims) but hardly dangerous. The worst offenders in that table (like sample codes E and I) I couldn’t find a match.

I’m sure the scientists did actually purchase them; however, they must have been in obscure corners of the Internet and certainly not something you’re going to buy by accident in the supermarket supplements aisle. This means concerns about the general population buying them by mistake are overblown.

Nonetheless, any manufacturer who deliberately adds other psychoactive ingredients–without clearly listing them on the label–is being dishonest and is part of the problem with the nootropics industry. I’m in support of studies finding bad actors and regulatory bodies putting pressure on them to act with integrity. What I’m not in favor of is intentionally using misleading language when reporting.

How to Report This Right

Bringing it together then, the data in the study is solid. The products that were deliberately mixed with other nootropics should be noted. At the same time, using provocative and misleading headlines just distorts the message. A much more accurate title is “4 Other nootropics found mixed with piracetam in cognitive supplements.” The original terminology has too strong of implications. For any layperson reading those articles, they’d think someone laced their fish oil with heroin or the like. More precise language will only help the field develop.

References

| ↑1 | Carroll, Linda. “‘Brain-Boosting’ Supplements May Contain Unapproved Drugs, Study Says.” Accessed January 29, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/brain-boosting-supplements-may-contain-unapproved-drugs-study-says-n1240880. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cohen, Pieter A., Bharathi Avula, Yan Hong Wang, Igor Zakharevich, and Ikhlas Khan. “Five Unapproved Drugs Found in Cognitive Enhancement Supplements.” Neurology: Clinical Practice, September 23, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000960. |

| ↑3 | links.lww.com/CPJ/A206 |